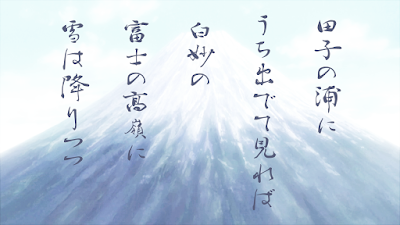

田子の浦に | Tago no ura ni |

うち出でて見れば | uchi idete mireba |

白妙の | shirotae no |

富士の高嶺に | Fuji no takane ni |

雪は降りつつ | yuki wa furitsutsu |

Yamabe no Akahito

Yamabe no Akahito 山部赤人 (dates uncertain) was a poet of early Nara Period (奈良時代 Nara jidai; 710−794). Although the dates of his life are uncertain, his works in Man’yōshū 万葉集 (Collection of Ten Thousand Leaves; finished around 759) can be dated between 724 and 736, and it is known that he was active in the court of Emperor Shōmu (聖武天皇 Shōmu tennō; 701−756, reigned 724−749).

Because he is not mentioned in any official histories, Akahito is presumed to have been a low-ranking official. However, his poems composed when accompanying Emperor Shōmu in imperial outings to Yoshino 吉野, Naniwa 難波, and Kii 紀伊 seem to suggest that Akahito could have been a court poet.

Akahito was active a little later than another famous poet Kakinomoto no Hitomaro 柿本人麻呂 (?−around 708; Hyakunin Isshu 3), and together with Hitomaro they came to be seen as the most prominent poets of the Man’yōshū period. Almost 200 years after Akahito, Ki no Tsurayuki 紀貫之 (866 or 872−954; Hyakunin Isshu 35) in the Kana preface (仮名序 Kanajo) of Kokinshū 古今集 (Collection from Ancient and Modern Times; 905) wrote:

It was impossible for Hitomaro to excel Akahito, or for Akahito to rank below Hitomaro.

(trans. McCullough 1985, 6).

Whereas Hitomaro’s poetry was praised for its sound, Akahito’s compositions came to be associated with imagery so rich, it was as if the poems were painting scrolls, where words were powerful enough to replace images.

Akahito's fame could be seen as continuing to this day and a considerable number of his poems has survived, including 13 chōka 長歌 (long poems) and 37 tanka 短歌 (short poems in 5-7-5-7-7 syllable pattern) in the Man’yōshū, as well as over forty poems in later imperial anthologies of waka (called chokusen wakashū 勅撰和歌集, chokusenshū 勅撰集 for short), although many attributions in chokusenshū are questionable.

Snow on the peak of Fuji

Akahito’s poem in the Hyakunin Isshu is highly visual and it introduces possibly the most monumental image in the whole collection − Mount Fuji (富士山 Fujisan). But whereas today the image of Mount Fuji is closely linked to Japan and is familiar to many, back in Akahito’s day it was part of an almost foreign landscape of the “eastern provinces” or Azuma 東国, that were far detached from the old Yamato 大和 province, modern-day Nara 奈良 prefecture, where the imperial court was located at the time.

Akahito’s poems are the first in Man’yōshū to mention Mount Fuji. And it is precisely poems, because the poem we now find in the Hyakunin Isshu is a variant of a tanka (short poem), which was originally an envoy (called hanka 反歌) to Akahito’s long poem (chōka) about Mount Fuji. Together, the poems are found in the third book of Man’yōshū (numbers 317−318), where with the headnote they read:

A poem with a tanka, composed by Yamabe no Sukune* Akahito upon looking at Mount Fuji in the distance.

| ||

天地の | Ametsuchi no | Since the time |

別れし時ゆ | wakareshi toki yu | when heaven and earth separated, |

神さびて | kamu sabite | divine, |

高く貴き | takaku tōtoki | lofty and noble, |

駿河なる | Suruga naru | Fuji’s peak |

富士の高嶺を | Fuji no takane wo | has stood in Suruga; |

天の原 | ama no hara | when one looks up |

振り放け見れば | furisake mireba | to the plains of heaven, there |

渡る日の | wataru hi no | the silhouette of the Sun, |

影の隠らひ | kage no kakurai | travelling the sky, is hidden; |

照る月の | teru tsuki no | invisible is the light |

光も見えず | hikari mo miezu | of the shining Moon; |

白雲も | shirakumo mo | even white clouds |

い行きはばかり | iyuki habakari | come to a halt; |

時じくそ | tokijiku so | and without care for the season, |

雪は降りける | yuki wa furikeru | snow has fallen. |

語り継ぎ | kataritsugi | Let us pass the word, |

言ひ継ぎ行かむ | iitsugi yukamu | continue to tell, of |

富士の高嶺は | Fuji no takane wa | this Fuji’s lofty peak. |

Hanka | ||

田子の浦ゆ | Tago no ura yu | Having crossed Tago Bay, |

うち出でて見れば | uchi idete mireba | looking up, |

真白にそ | mashiro ni so | pure white |

富士の高嶺に | Fuji no takane ni | is Fuji’s lofty peak, |

雪は降りける | yuki wa furikeru | where snow has fallen. |

By the time the Hyakunin Isshu poems were selected, the practice of writing long poems had long ceased, and the short poem (tanka) was well-established as the prevalent mode of poetic composition in Japanese. It could have been for this reason that what was once an envoy to a long poem came to be seen as a standalone work, which was included among winter compositions in Shinkokinshū 新古今集 (New Collection of Poems Ancient and Modern; officially presented in 1205, finished around 1216).

By the time it was selected for Shinkokinshū, Akahito’s poem, much like the composition of Empress Jitō (持統天皇 Jitō tennō; 645–702; Hyakunin Isshu 2), had undergone changes, and it was this newer variant that was also included in the Hyakunin Isshu:

田子の浦に | Tago no ura ni | Coming out on Tago Bay, |

うち出でて見れば | uchi idete mireba | looking up, |

白妙の | shirotae no | linen white |

富士の高嶺に | Fuji no takane ni | is the lofty peak of Fuji, |

雪は降りつつ | yuki wa furitsutsu | where the snow continues falling. |

The old Akahito’s poem from Man’yōshū is realistic. It is as if he comes out (uchi idete) of (yu) the Tago bay (Tago no ura) in the old Suruga 駿河 province (present-day Shizuoka 静岡 prefecture) − crosses it, − and when he looks (mireba) up, he sees the pure white (mashiro) peak of Mount Fuji (Fuji no takane), where snow (yuki) has fallen (furikeru) and accumulated. It is a picturesque scene which comes into view line by line.

Meanwhile, the newer variant of the poem, is an image nonetheless, but an idealised, maybe almost a magical one. Here, the lyrical subject comes on Tago Bay (Tago no ura ni) and sees a linen white (shirotae no) peak of Fuji (Fuji no takane), where the snow continues falling (furitsutsu). It is as if the lyrical subject can see the snow accumulating with time. But in an idealised image, the place of Akahito’s Tago Bay (田子の浦 Tago no ura) becomes unclear and we are uncertain whether the current Tago Bay is the same place, − probably not. And the whiteness is different − shirotae no, which indicates white colour, is a makura-kotoba 枕詞 or a pillow word, which is a fixed expression, that has at least partly lost its true meaning. Shirotae no usually precedes words like snow (雪 yuki) or clouds (雲 kumo), but also robes (衣 koromo) or sleeves (袖 sode), so the whiteness of shirotae no is often understood and translated in relation to white fabrics, and this adds to the newer poem's slightly different overtones.

Whereas the older Man’yōshū poem is picturesque, as if one was looking at a hanging scroll, the newer Shinkokinshū variant is more like a movie − a very modern thing, I understand, − but one can almost feel when reading that lyrical subject is as if in a movie, coming out on Tago Bay and [maybe] through fast motion witnessing white snow piling up on the divine, lofty and noble, peak of Mount Fuji. Surely, this image over a thousand years ago must have seemed magical.

Akahito’s image of Mount Fuji remains as accurate today as over a thousand years ago, − vivid, stunning, and unmistakable. And probably as long as it stands − the mountain that has no equals − people will continue telling of it, just like Akahito encouraged.

Notes

* Sukune 宿禰 was the third highest of the eight hereditary titles (八色の姓 yakusa no kabane), designated by Emperor Tenmu (天武天皇 Tenmu tennō; ?–686) in 684.